By Kathleen Biggins

Have you heard? Electric vehicles are toast! No one is buying them, chargers are non-existent, and buyers are full of remorse. The Biden administration has been thwarted and our gas-powered cars are saved!

Or so conservative pundits and some media sources tell us…

But, in fact, this narrative of demise is way overhyped and ignores two critical realities: we need this transition to work quickly or we will lose other things we love much more than our gas cars; and EVs are more highly evolved than gas-powered cars, so once transition kinks are resolved, buying electric will bring more pleasure than sacrifice.

Fossil fuels come with a big, hidden price that taxpayers have to pay. Gas-powered

engines are directly responsible for much of our climate-change risk, and transportation is the number one greenhouse gas-emitting sector in the United States. If we maintain the status quo, we will pay significantly for it in disruption to our economy, investments, real estate, insurance coverage, health costs, and food and water systems.

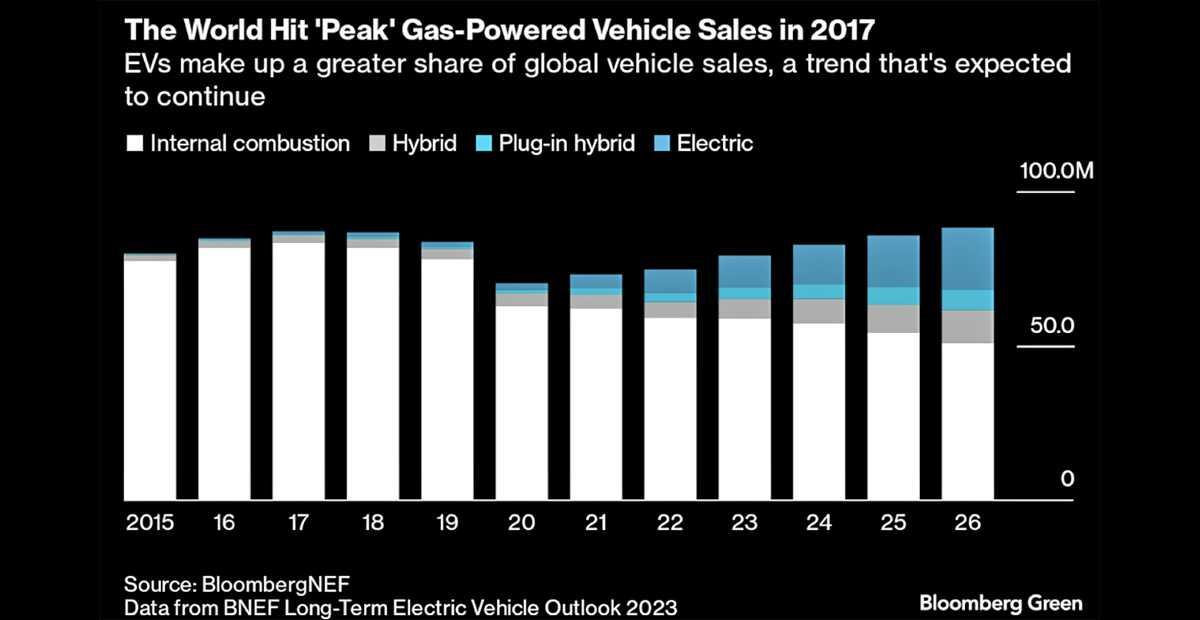

Let’s look at global trends. EVs are still replacing internal combustion engine cars (ICEs) across the world at a rapid clip. In 2020, EVs made up 1 in 25 new cars sold globally. Today it is almost 1 in 5. In fact, as this chart shows, ICE sales began to decline all the way back in 2018.

Even in the U.S., EV growth is continuing (up 5.9% versus 2022 according to Kelly Blue Book estimates), with fourth-quarter sales in 2023 setting a record for both volume and share. However, the rate of growth has slowed versus 2022, and significant headwinds exist, threatening to make the U.S. an outlier to global trends.

What’s going on here? First, in the United States, there have been fewer models of EVs and they are still more expensive to buy than their ICE counterparts. Second, charging takes a while and range anxiety is real, especially for those who drive long distances. Third, like almost everything else in our society, EV ownership is being pulled into the partisan culture wars.

But some of that is about to change.

Battery costs continue to decrease (with Goldman Sachs projecting costs in 2025 to be 40% cheaper than in 2022) and market competition is driving purchase costs down. This means electric cars will be at parity with gas-powered cars – or cheaper – around mid-decade and will not need subsidies to compete on price.

In addition, Americans now have a much greater variety of EVs to choose from. In 2024, new car buyers will have more than 300 EV options to consider, ranging from the $28,000 Nissan Leaf to the $422,750 Rolls Royce Spectre. With fewer parts, EVs are easier and cheaper to maintain than a similar gas-powered car. According to a 2023 University of Michigan Transportation Research Institute study, 90% of Americans would save money switching to an EV versus driving a similar gas-powered car.

Now, let’s consider charging anxiety.

Some people are turned off from EVs because they think they’ll lose a lot of time charging their vehicles or will experience difficulties charging on a trip. But most of the time, EV drivers actually save time by avoiding gas stations, oil changes, and other maintenance. Since 80% of American EV owners install a home charger, they can top off their cars every day, similarly to how most of us charge our cell phones. Clearly, apartment dwellers without charging stations or those unable to afford a charger find this process much more expensive and inconvenient.

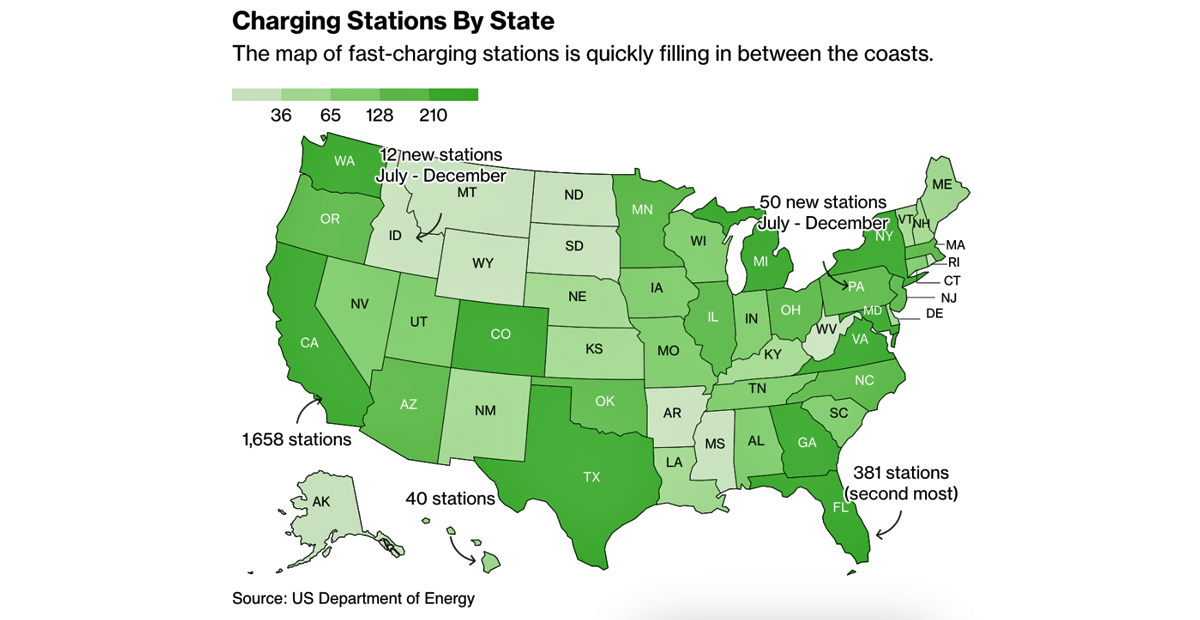

Battery ranges also have increased – the average charge for EVs in 2023 can match distances provided by a full tank of gas in most cars (approaching 300 miles per charge, with some luxury EVs providing more than 500 miles per charge). And battery ranges are expected to keep increasing. That means range anxiety is limited mostly to long trips. While it’s true that the infrastructure is not yet where we need it to be to support the transition, it continues to grow at a rapid pace – the number of public fast-charging stations has increased 70% from 2021, finally populating highways across the South and Midwest where there has been a noticeable lack to date.

That leaves political partisanship, which during an election year could be substantial. EV sales currently skew toward Democratic areas (which also often have higher gas prices and stronger EV subsidies on the state level). EV and battery “bashing” is common among conservative pundits, with the presumed Republican presidential nominee, Donald Trump, purportedly claiming EV drivers should “rot in hell” – an interesting perspective given that many EVs and batteries are built in red states.

But at the same time, there is a much bigger group of Americans recognizing the risks of climate change. For the growing cohort that is concerned about the issue now (about 64% of the U.S. population, according to a recent Yale study) or concerned it will harm future generations (70%), driving an EV can be an easy and substantial way to cut personal emissions and to signal to others that they have done so.

Our takeaway? There will be potholes and we may have to downshift to overcome obstacles in the road, but we are on our way. EVs are simply a more highly evolved type of car, an improvement on the gas cars of yore. Like any new technology, there is room for improvement, but EVs are already more agile, faster, quieter, cleaner, cheaper to fuel and maintain, and can last much longer than gas-powered cars. As technology is upgraded, purchase costs decline, and charging networks expand, EVs should become an easy choice for the majority of drivers, even conservative ones.