Dear Friends,

Last week’s extreme rainfall in the New York region and Libya’s almost unfathomably tragic dam breaks in September show our stark reality: nature is playing by a new set of rules. Our infrastructure, built for yesterday’s climate, is no match for today’s climate challenges, much less tomorrow’s. We are all vulnerable, whether we live in the global north or south, in cities or in rural areas. The hallmarks of our changed climate – extreme rain floods, intense heat waves, higher sea surges, stronger hurricanes, more widespread wildfires, increased exposure to disease – threaten us all.

But it’s not just physical risks: it is increasingly clear that climate change directly threatens our economy and our financial systems. The U.S. has experienced 23 large natural disasters (each costing more than $1 billion) this year so far, months ahead of the culmination of our hurricane season. While it is true more of us are living in exposed areas, these big events are happening more frequently and often pack a stronger punch because of climate change. In fact, the relatively new science of attribution allows us to quickly identify when climate change exacerbates or enables these disasters, and the data is damning. For example, the research shows the Libyan floods were made 50 times more likely due to climate change and the heat levels this summer across the U.S. Southwest would have been virtually impossible before humans warmed the planet by burning fossil fuels. And the rain that inundated New York last week showed that even in cities that have hardened their infrastructure, we are nowhere near prepared for what’s coming at us, fast.

This has real implications for the insurance industry. When the real price of the risk is factored in, the costs are too high for many to afford. In addition, insurance companies are leaving vulnerable places in droves, deeming them “uninsurable.” This reckoning – the realization that our risks can no longer be predicated on the past because we have so radically changed the norms in our future – is coming not just for insurance, but for housing, construction, and investment markets as well. The economic, legal, and fiduciary risks will be significant for those who don’t, or won’t, factor in the new norms when the science and evidence are so clear. Importantly, this recognition of the tie between fossil fuel emissions and climate change damage is gaining traction in the court system, both globally and in the United States.

Yet despite the mounting evidence of a chaotic future if we don’t change our emissions path, we remain divided. Some push for innovation, others defend the status quo. Take a look below to see the latest trends pushing us forward and those holding us back.

Sincerely,

The C-Change Conversations Team

Notable Quote

“The bottom line is that we have infrastructure in New York, infrastructure all across the U.S. and frankly in many, many parts of the world that is just simply not capable of withstanding the climate that we’re seeing today and certainly not the climate that is yet to come in the future.”

–Steve Bowen, chief science officer for Gallagher Re,

a global reinsurance broker

News of Concern

Let’s not mince words: right now we are losing the race to keep the planet at safe temperature levels. In its report card on global progress toward the goals of the 2015 Paris Agreement, the United Nations issued a dire warning in September: slash emissions drastically and rapidly – 43% by 2030 and 60% by 2035 (compared to 2019 levels) – or the planet will warm beyond the 1.5°C (2.7°F) threshold that scientists say is crucial to keep climate catastrophe at bay. For reference, our current temperature is 1.1°C higher than before the Industrial Revolution and the climate impacts are already evident all around us – and will get more severe even if we can hold at that 1.5°C goal. And 2023 is on track to be one of the hottest years ever recorded.

One of climate change’s most dangerous impacts is on our water supply – it paradoxically can give us too much water (extreme precipitation), too little water (enhanced drought), and water that is too dirty (minerals and toxins concentrated in depleted aquifers and contaminated floodwaters). Two new reports show how dangerous to humans these water problems can be. The first shows how dramatically our aquifers are being depleted, in part from overuse and in part because climate-enhanced droughts provide less water to replenish them, threatening farms and communities across the country. The second shows that the mighty Mississippi River is so low due to drought conditions that fresh water intakes and supplies are compromised in the New Orleans area by salty sea water intrusion. As sea levels rise and rain becomes less reliable, aquifer depletion and saltwater intrusion look to be ongoing problems that could be incredibly challenging, especially in the parts of the world without the money or resources to create the new infrastructure necessary to meet this challenge.

Nor can we seem to win our war against disease-carrying pests like ticks, fleas, and mosquitoes, which are expanding their geographical footprints and are active longer through the year in a warming climate. We’ve seen threats in the U.S. from “new diseases” like West Nile, chikungunya, and dengue that have spread north from the tropics. But this year, concerningly, an old scourge – malaria, considered to be eradicated from our shores in the 1950s – is back, spreading by mosquitoes in Texas, Maryland, and Florida, and anticipated to spread along our southern shore states. The threat is compounded by the fact that mosquitoes are evolving to resist insecticides and other control methods.

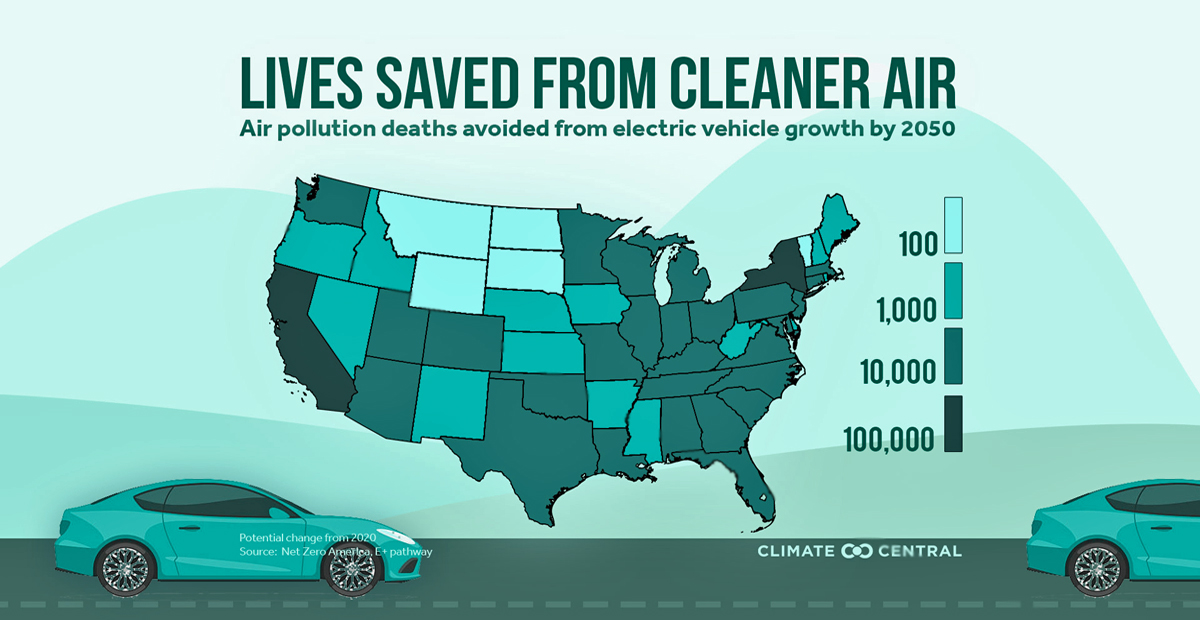

There’s a different battle happening in Detroit, as the United Auto Workers strike against General Motors, Ford, and Stellantis shows just how hard this transition can be. Electric vehicles are cheaper to fuel and maintain and are dropping in price, making them more attractive to American consumers. Sales have increased 48% this year in the U.S. compared to 2022 and the transition is critical to our emission goals. The transition to EVs will lessen pollution (and save lives, as you’ll see in the graphic below) and strengthen our economy in the long run. But in the short term, workers who built car parts that are no longer needed, or who work at factories that are not attracting the new technology, are at risk. This will play out in other industries as well, as legacy approaches are disrupted, and the very human toll of it needs to be acknowledged, planned for, and managed.

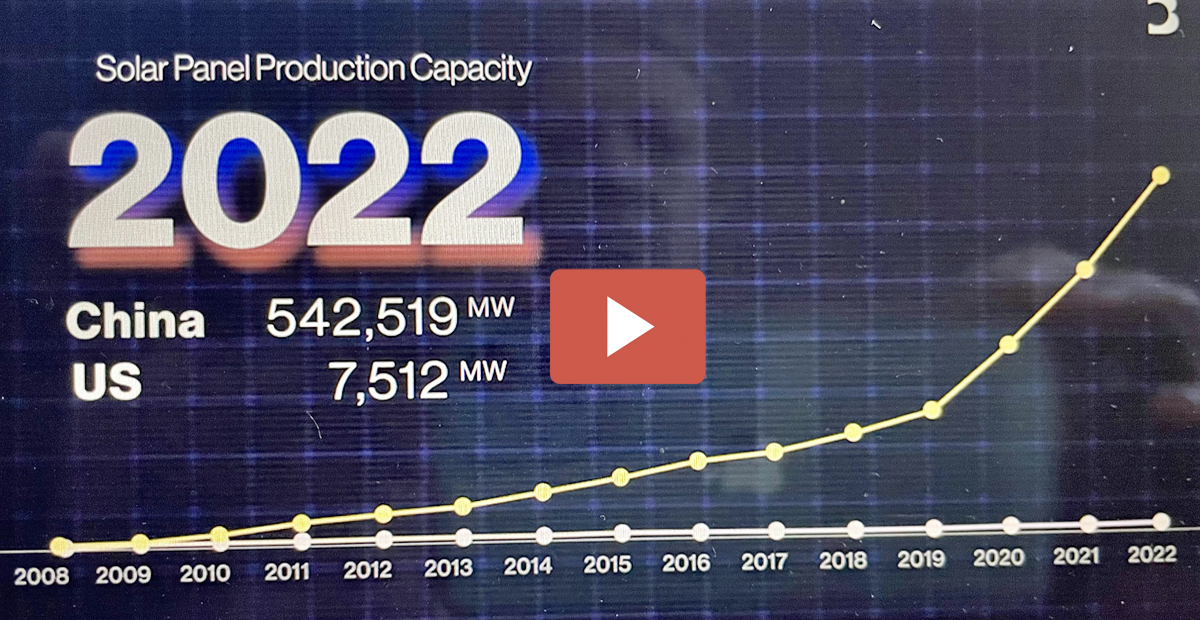

It is important to recognize that this transition isn’t just happening in our country but across the world, and we are significantly lagging behind the market leader, China. After decades of industrial planning, China now controls clean-tech supply chains and has created massive economies of scale for clean-tech manufacturing. Any slowing of U.S. investment, including in the EV arena, will put us further behind.

News of Hope

Despite these challenges, the world is waking up to the need to accelerate the transition. A newly revised landmark net-zero report from the International Energy Agency shows the pathway to net zero by 2050 has narrowed but is still possible, buoyed by the drop in price and growth of renewable energy. G20 leaders also recognized the threat, agreeing to triple global energy capacity by 2030 to $4 trillion to try to meet the goal of limiting warming to 1.5°C. While we are investing more today globally in renewables than fossil fuels ($1.7 trillion vs. $1 trillion in 2022) and clean energy jobs now make up 50% of all energy jobs globally, we need to do more. Luckily, renewable energy is now significantly cheaper at a utility scale than its fossil fuel competitors, and new transmission and storage technologies are allowing it to handle increasing levels of our energy load.

It is worth nothing that younger people – who will be more exposed to climate risk later in the century and who are projected to become the biggest voting block in the U.S. this decade – are raising their voices, as was evident in the protests around the world in conjunction with Climate Week, a UN-partnered event in September in New York City. Research shows that climate change is a top concern for 18- to 29-year-olds, including among young conservatives, and that young people who care about climate change are more politically active.

Intriguingly, this is happening at the high school level as well. Students at 50 U.S. high schools are launching an initiative to bring workforce development, climate curriculum, and clean energy to public schools. This is critically important – just as nature is playing by new rules, humans will need to prepare differently for the challenges and opportunities ahead. China is way ahead of us in reconfiguring its education system and training its young people for jobs in the new clean-tech economy.

That’s why we are so encouraged by the inauguration of the American Climate Corps, a program the White House says will create 20,000 jobs in clean energy and climate resilience in its first year and train workers for a future in clean tech.

And the clean energy innovation continues to impress. Not only has it delivered the cheapest utility energy humans have ever experienced, with the opportunity to continue to become significantly cheaper by the end of the decade, new processes and approaches offer tantalizing gains. So often, new clean technology gets big pushback – no one wants to see solar or wind tech in their landscape – but we forget that these ideas are just seeds. They’re going to grow and improve, like floating wind turbines that could move a coastal controversy off the landscape. They’re going to push the envelope, like this first-ever partnership of fusion and industry, to make steel with what once seemed like the stuff of science fiction.

Notable Video

This mini-documentary by Bloomberg Originals takes a look at how the U.S. has fallen behind China in the production of solar panels, the cheapest and fastest growing form of utility energy – and what that means for our future.

Notable Graph

As the auto industry grapples with a difficult transition to EVs, it’s worth noting that electric vehicles will not only reduce carbon emissions, but will also save lives. And ultimately, that’s what this is all about.