By Nancy Ylvisaker

Carbon markets were an important topic at the COP28 climate talks in Dubai and will remain so for the foreseeable future as nations seek to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. To help us understand this critical area, we’ve asked our team member Nancy Ylvisaker to explain both the promise and the peril of this burgeoning sector, and to review some of the decisions made at COP28. Nancy is a former executive at J.P. Morgan as well as a nonprofit leader who has a graduate degree in business from Yale. She recently completed a Yale graduate program in clean energy finance.

The next decade is a critical one for the climate. Scientists universally agree we must halve global emissions by 2030 if we are to keep the warming of the planet under 2°C (3.7°F) – the threshold beyond which Earth will experience catastrophic consequences. To reach these climate goals, 198 nations signed the 2015 Paris Agreement, which requires them to track and report their carbon emissions and their activities to reduce and offset them. And 145 countries have pledged to reach net zero by 2050, and they are creating policies and investing billions of dollars to get there.

Nations are looking to the vast power of the markets to help them decarbonize. Carbon markets put a price on carbon emissions – charging companies for the carbon dioxide (CO2) they emit – to incentivize businesses to cut their emissions where and how it is most effective. The core of the system involves pricing and trading of carbon credits. A carbon credit represents one metric ton of CO2 or a CO2 equivalent (CO2E) removed from the atmosphere (or avoided for at least 100 years). How much is a ton of CO2? The amount generated by driving a car 2,500 miles. Credits are interchangeably called offsets because companies use them to offset emissions from their operations.

Carbon markets can be either voluntary or compliance-based (mandated by the government). Their rationale is similar to that of other markets: whether trading currencies, oil, or wheat, the idea is to create efficiency, facilitate transactions, and standardize prices. In Part 2, we focus on compliance markets; in Part 1, we took a look at voluntary markets.

The Compliance Markets/Cap and Trade

While voluntary actions to reduce or offset CO2 will continue, governments around the world will have a critical role going forward. To put it simply, without regulations and caps on emissions, many companies, utilities, and municipalities don’t have an incentive to pay to reduce their emissions.

The most commonly used compliance system, now implemented or being considered in more than 40 nations, is called cap and trade. Governments (or regulators) set a cap on the amount of CO2 or CO2E that companies can emit. Companies must buy a set number of permits, or credits, that allow them to emit a specific amount of CO2. (Again, one credit equals one ton of CO2.) If a company doesn’t need all of its credits because its emissions are below its cap, it can trade them for financial compensation to a company whose emissions exceed its cap. Each year, the cap on emissions gets stricter – and the shrinking pool of permits therefore gets more expensive. This incentivizes companies to cut emissions by operating more efficiently and investing in alternative technologies. The more they lower emissions, the fewer permits they need to buy – or the more they can sell or trade.

The idea for cap and trade originated in the U.S. in the 1980s. Sulfur dioxide from power plants, when combined with oxygen and water in the air, was producing highly acidic sulphuric acid – called acid rain – that was damaging forests and killing aquatic life. It was clear that regulations were needed to direct power plants to cut pollution, but there was concern that costs would drive up rates for consumers. There also was worry that a one-size-fits-all regulatory approach would be heavy-handed and wouldn’t allow companies to tailor their own strategies to reduce emissions. So with the passage of the 1990 Clean Air Act, a cap and trade system was created that put a limit on allowable emissions and permitted companies to use market mechanisms to reduce emissions. Within eight years, acid rain decreased by 20%.

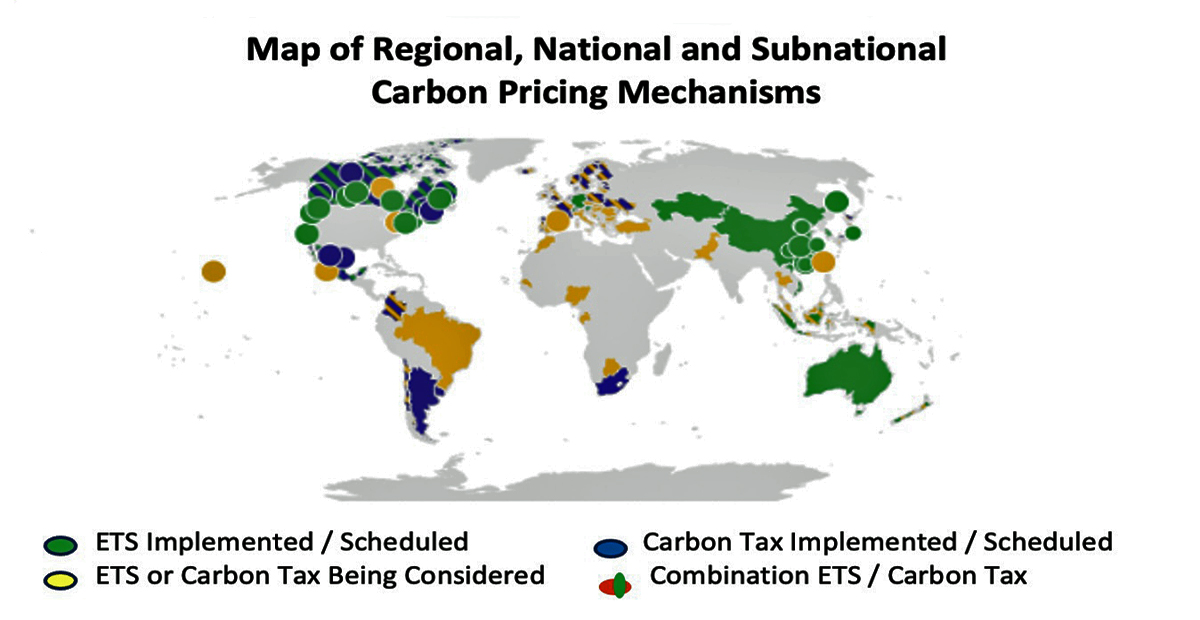

Cap and trade systems are now being used all over the globe, covering about a quarter of world markets. While not all nations’ systems are at the same level of development, it is clear that advancement happens quickly when countries discover what is most effective for their needs. The map below shows where cap and trade initiatives are in place (green and blue) or under consideration (red and yellow).

Note: ETS stands for Emissions Trading System, another term used for cap and trade.

The EU – Global Leader in Emissions Reduction

Founded 20 years ago, the EU’s carbon cap and trade market is the oldest and largest in the world, with 87% of global volume (about $790B in 2022). It covers power plants, heavy industry, and transportation – almost half of the EU’s CO2 emissions, with other industries to be phased in.

The EU’s record is impressive: emissions have fallen 32% since 1990. And as the imperative of reaching net zero becomes more urgent – and nations fall behind on pledges – the EU is doubling down on its commitments. This year, its emissions cap will begin reducing twice as fast – 4.4% per year. It also has amended its legally binding Climate Law to require by 2030 a 62% (from 55%) reduction in emissions, and a 45% (from 32%) increase in renewable energy investments.

With the daunting goal of achieving another 30% reduction by 2030 – just six short years away – prices paid for permits tripled between 2020 and the end of 2023, rising from $26 to $80 per ton. This dramatically increases financing for clean-energy investment and incentivizes companies to cut emissions.

The following chart shows the world’s largest compliance markets by size, and demonstrates the significant edge held by the EU.

The United States – State and Regional Approaches

Although the U.S. has discussed implementing a national cap and trade system, the idea has never gained traction in Congress. In 2022, legislators flirted briefly with cap and trade but instead implemented the tax-incentive approach of the Inflation Reduction Act. But large-scale cap and trade programs are already operating in industry and at state levels, reducing emissions and providing testing grounds for national systems should they arise. There are three primary cap and trade programs operating in the United States:

1. RGGI

The original cap and trade program in the U.S. is the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (RGGI), a collaboration of 12 New England and Mid-Atlantic states that have worked together since 2009 to cut greenhouse gas emissions from power plants. Each year, RGGI sets a cap on total emissions for the combined power sectors, and plants must buy one credit for each ton of CO2 they emit. The cap lowers 3% per year. Despite several political challenges, RGGI has contributed hugely to tackling climate change issues in the region. Regional emissions have declined 50% – two times faster than in the rest of the nation. And quarterly credit auctions have generated more than $6 billion for renewable energy and energy-efficiency programs. Credit prices are a function of energy costs and demand, but RGGI also has managed prices to avoid rapid rate hikes to consumers and to give companies time to build clean energy infrastructure.

2. California

California set the first statewide limit on greenhouse gas emissions in 2006 and piloted its cap and trade system in 2013. It regulates 450 large companies that create 85% of the state’s emissions. Quarterly credit auctions have generated $24.3 billion for clean energy and improving community health and transit systems. By law, 35% of revenues go to environmentally disadvantaged and low-income communities.

Like the EU, California has set a daunting challenge for itself. In the 10 years since inception of its program, it has cut emissions 15% (from 1990 levels) – and its goal is to reach 48% by 2030. While the state’s cap will decline by 3-3.5% per year, and the state has a suite of other initiatives, it appears unlikely to be enough. In addition, there are structural issues, discussed below, that California and other states (and nations) must address if they hope to achieve their emissions reduction goals.

3. Washington

Launched in January 2023, Washington’s carbon markets cover 100 businesses responsible for about 75% of the state’s carbon emissions. It is too soon to estimate emissions reductions, but auctions have generated $1.5 billion to fund climate solutions. To make up for its later start, Washington has set even more rigorous reduction goals than California’s and will require cuts in emissions of 7% each year through 2030. As in California, 35% of revenues are invested in vulnerable communities.

Many other countries are implementing some form of carbon markets, including Canada and nations in Africa and South America. The rising powerhouse, though, is China. Once its new market is fully implemented, it will cover companies emitting more than three times that of the EU; this will move the dial significantly on emissions reductions.

Structural Changes Needed for Market Success

Compliance markets continue to grow and become more precisely calibrated with experience. But to achieve international climate goals, the markets need widespread adoption, and they must be integrated across national and international markets. Currency and commodity markets trade globally because of uniformly applied pricing standards. The carbon markets aren’t quite there yet.

This lack of common standards results in what is known as carbon leakage: companies in nations or states with emissions caps that result in higher production costs circumvent the law by moving production to a location with less-strict emissions laws – avoiding the costs of compliance. This climate compliance “cheating” results in a triple whammy of negative effects.

It means 25-30% of emissions aren’t covered by regulation – and the costs the emitters should pay through carbon taxes “leak” out of the system.

The “cheaters” reap financial rewards because they aren’t paying the cost of their emissions.

Carbon leakage hamstrings whole systems: to avoid the risk of losing businesses, almost all cap and trade systems around the world have exempted – or subsidized with lower carbon prices – these large companies that operate partially in geographies where they aren’t subject to emissions caps.

After years of debate, in 2023 the EU passed a Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism – essentially a tariff on goods imported from nations outside the EU that don’t charge companies for the cost of their pollution. The tariff will level the playing field. All companies will pay for their emissions, either via carbon pricing in their own nations or through border taxes when their goods enter EU markets.

But the issue remains a problem in the United States. California exempts big emitters with multi-state operations that could evade paying for emissions by relocating. In Washington State, the problem may be even larger. Its new cap and invest program (so called because the proceeds are invested in community programs and renewable energy) set much stricter emissions limits than those in California, resulting in high demand – and significantly higher prices – for credits as companies scrambled to comply. This puts Washington at the same risk as California: that companies could migrate elsewhere to avoid higher costs. In the end, it creates a race to the bottom, and ill-will between companies who receive – or don’t – a free ride.

In 2011, California and Quebec re-launched the Western Climate Initiative Cap and Trade system (previously a larger group including Mexico and multiple U.S. states and Canadian provinces), recognizing that cooperation between their economies on emissions would be central to decarbonizing efforts. Washington is a member as well, and Oregon may join as its own cap and trade program expands. While California and Quebec have had successful joint auctions since 2011, generating almost $8 billion for climate and efficiency programs, initiative membership in Canada has waned from four provinces to only one. Any growth will likely be from new members in the United States.

The Future of Carbon Markets

The carbon markets have grown and matured dramatically in the last several years, proving to be important tools in the fight against climate change. The voluntary markets have encouraged carbon-conscious behavior, giving corporations – and individuals – a way to offset emissions and provide capital to developing nations, while advancing longer-term reduction strategies. They serve an important transition role as governments implement large-scale compliance markets. Over the long term, broad implementation of compliance markets, with their mix of mandatory regulations and market mechanisms like cap and trade, will be essential to global achievement of net-zero goals.

In Part 1, we take a look at Voluntary Markets. Click here to read the full article.