By Nancy Ylvisaker

Carbon markets were an important topic at the COP28 climate talks in Dubai and will remain so for the foreseeable future as nations seek to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions. To help us understand this critical area, we’ve asked our team member Nancy Ylvisaker to explain both the promise and the peril of this burgeoning sector, and to review some of the decisions made at COP28. Nancy is a former executive at J.P. Morgan as well as a nonprofit leader who has a graduate degree in business from Yale. She recently completed a Yale graduate program in clean energy finance.

The next decade is a critical one for the climate. Scientists universally agree we must halve global emissions by 2030 if we are to keep the warming of the planet under 2°C (3.7°F) – the threshold beyond which Earth will experience catastrophic consequences. To reach these climate goals, 198 nations signed the 2015 Paris Agreement, which requires them to track and report their carbon emissions and their activities to reduce and offset them. And 145 countries have pledged to reach net zero by 2050, and they are creating policies and investing billions of dollars to get there.

Nations are looking to the vast power of the markets to help them decarbonize. Carbon markets put a price on carbon emissions – charging companies for the carbon dioxide (CO2) they emit – to incentivize businesses to cut their emissions where and how it is most effective. The core of the system involves pricing and trading of carbon credits. A carbon credit represents one metric ton of CO2 or a CO2 equivalent (CO2E) removed from the atmosphere (or avoided for at least 100 years). How much is a ton of CO2? The amount generated by driving a car 2,500 miles. Credits are interchangeably called offsets because companies use them to offset emissions from their operations.

Carbon markets can be either voluntary or compliance-based (mandated by the government). Their rationale is similar to that of other markets: whether trading currencies, oil, or wheat, the idea is to create efficiency, facilitate transactions, and standardize prices. In Part 1, we take a close look at voluntary markets; in Part 2, we focus on compliance markets.

The Voluntary Market for Carbon Credits![]()

Many of the world’s largest companies are working voluntarily to compensate for, or offset, their own emissions. Frequently they are responding to shareholder pressure to adopt net- zero policies as well as their own sense of urgency about climate change. There are three main types of voluntary credits:

- Avoidance credits make up more than 75% of the market, and are generated by activities that prevent carbon emissions from occurring. For example, companies in developed nations get credit for preventing future emissions by protecting forests from being cut down, or by investing in renewable energy projects that will avoid future greenhouse gas emissions. Buyers pay for these projects and then count them as offsets to their own carbon footprints. In the last few years, the sale of these offsets has become an important source of decarbonization finance for developing nations rich in natural resources, such as rainforests and mangrove swamps, which are highly efficient at absorbing CO2.

- Carbon reduction credits, which make up about 20% of the market, are generated by activities that reduce emissions. Examples include improving fuel efficiency or implementing programs that reduce the release of methane gas by capturing it at the source.

- Removal credits, which ameliorate the impact of past emissions, make up less than 5% of the voluntary market. Reforestation – planting new forests to sink carbon – is in this category. So are technologies like direct air capture (DAC) and carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS), which remove carbon from the air or from industrial processes and sequester it underground. But these are still in very early stages, are exceedingly expensive, and remove only a few thousand tons of carbon a year.

Growth – and Growing Pains

The voluntary carbon market has taken off in the last 10 years: 42% of Fortune 500 companies had some form of credits in 2022, and the market quadrupled in four years. Total volume was around $2 billion last year according to Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF), and is projected to grow to $10B to $40B by 2030. The airline and auto industries, with their large public presence – and large emissions footprints – are the largest investors. Overall, almost half of the voluntary market is comprised of nature-based projects; research suggests natural climate solutions such as planting and restoring forests, grasslands, and mangroves, along with better managed farmland, can generate 30% of the emissions reductions needed to keep global temperatures from increasing more than 2°C.

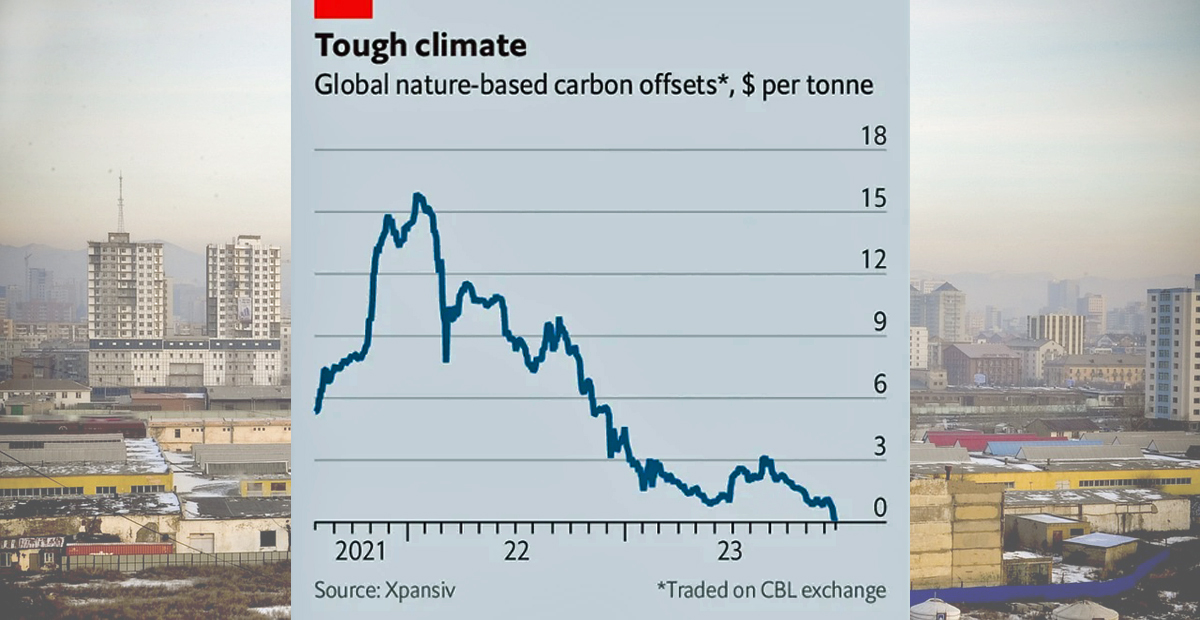

But after soaring for the last few years, the voluntary markets declined in the first half of 2023, hurt by highly publicized instances of shoddy deals and misrepresentation. For instance, some forests were counted as “preserved” when they were already protected in state forest programs and so not at risk. In other cases, projections for the amount of CO2 a forest could sequester were vastly overstated as forests were planted with monocultures or non-native trees, and some were neglected or even bulldozed. Problems reflect the undefined “Wild West” character of many early stage markets, but also the low-cost window dressing by purchasers eager to burnish their public images. Some nature-based credits were sold at such low prices – $2 to $8 per ton – that they couldn’t possibly deliver the benefits promised. The graph below shows the steep decline in these prices over the last several years.

Without reliable project standards, measurement tools, and due diligence, companies have become wary of being accused of greenwashing and are deeply concerned about their reputations being tainted by misleading or failed projects. Nestlé, Gucci, EasyJet, and others have recently said they would no longer use carbon offsets. Others are staying on the sidelines while industry governance groups such as Verra and the Carbon Credit Quality Initiative work to codify “core carbon principles” – benchmarks for quality, transparency, and permanence. Additionality is a key requirement – projects must create new decarbonization benefits beyond what was already taking place.

Developing Counties – Keeping their National Treasures

Developing nations rich in the forests, grasslands, and marshlands that are so critical to planet health – and that keep carbon in the ground – are also re-evaluating participation in credit projects. Haphazardly structured deals sold at low prices harm developing nations as well. And the importance of natural assets is increasingly recognized; some analysts equate the value of these carbon sinks to precious resources like lithium, copper, or oil.

Zimbabwe and Kenya recently announced that they will require that 50% of carbon revenues generated be kept in their national treasuries. Indonesia and Honduras have put moratoriums and restrictions on the sale of forest-based carbon credits – many sold by developers more interested in taking fees than in maximizing returns to the local economy through better-structured, higher-priced deals. In addition, as public expectations for climate goals ratchet up, developing nations want to apply carbon offsets generated by their rich natural resources toward their own national climate pledges under the Paris Agreement – not see the credits transferred to developed nations.

Stumbling Blocks for Market Growth

There was a great deal of debate leading up to COP28 on whether the market should be focused on nature-based credits or on technology-based CO2 removal solutions. The United Nations and many developing nations have stated strongly that the voluntary market should stay focused on nature-based credits, which provide urgently needed funds to these nations for land protection and sustainable development work they could not otherwise afford. The UN also has expressed concern that carbon removal technologies like DAC are too expensive and remain unproven technologically.

In contrast, the EU and the International Panel on Climate Change view removal technologies like DAC as absolutely necessary tools in the arsenal of strategies to address climate change in the medium to long term. Concerned about over-reliance on nature-based credits, this year the EU will require companies to report emissions before factoring in offsets, trying to spur more aggressive investment in removal technologies. However, most market experts agree on the long-term importance of DAC and other technology-based offsets. They view investing in nature-based solutions as a transition, or bridge, while the technology ramps up for DAC, CCUS, and other nascent carbon removal industries.

COP28 – Driving Toward Solutions

Discussion of these issues was front and center at COP28 in Dubai. While an initial UN proposal called for allowing only nature-based credits, the final resolution at COP28 adopted a neutral approach that doesn’t distinguish between nature-based and engineered solutions.

Another key priority debated heatedly was structuring an international trading exchange for national-level credits. This would further impart standardization and transparency, and open the gates to the huge growth projected in the market. According to BloombergNEF, the market could rocket to close to $50B by 2030. By 2050, Bloomberg estimates the total market could reach almost a trillion dollars.

Despite significant debate, the parties at COP28 could not agree on key rules for trading offsets. Some parties – including the United States – wanted more limitations on oversight and regulation to support market growth. Others, including the EU and developing nations in Africa and Latin America, wanted stronger regulations and greater deal transparency to prevent continued churning out of the junk deals that have chilled the market to date. Issues were not resolved, and the debate was kicked forward to COP29.

But they did take important action that will provide much-needed clarity and guidance for buyers, developers, and the markets overall. Some of these actions include:

- The Voluntary Carbon Markets Integrity Initiative (VCMI), the Science Based Targets initiative, and the Greenhouse Gas Protocol announced an “end-to-end integrity framework” to provide guidance to corporations on defining and using high-quality voluntary credits to address their emissions.

- Six top-rated carbon-crediting organizations, including Verra, Gold Standard, and Global Carbon Council, announced a joint framework providing common standards for transparency, credit integrity, and measurement consistency. This is critical for confidence in a growing market.

Another critical next step for the markets to get to scale is aligning regulated financial markets with the carbon markets. COP28 delivered through these actions:

- The Commodity Futures Trading Commission in the U.S. published a set of voluntary carbon credit trading guidelines that dovetail with principles of transparency of the VCMI.

- The International Organization of Securities Commissions (IOSCO) – the global standard setter for the securities industry – issued 21 principles for carbon market integrity.

Progress on setting these international standards has increased market confidence despite the lack of success in creating a national-level trading platform. As a result, nations are moving ahead with large transactions and building local trading platforms that can be more easily integrated into international platforms as they come to fruition in the next year. Overall market volume is increasing again after the declines in 2022 and 2023. As an example, Tanzania announced a deal at COP28 covering six national parks across 1.8 million hectares (4.4 million acres) following an announcement that more than 20 companies are investing in $20 billion of credits.

From Nature to Technology

As discussed, the voluntary market is set for huge expansion. In addition, BloombergNEF and others predict that a decade out, the voluntary market will shift largely to expensive, technology-based credits that remove carbon; by then, they believe, many of the critically significant natural assets will likely be protected using nature-based credits, and renewable energy technologies will be at scale and in rapid deployment.

The impact on prices will be huge. The graph below illustrates the all-over-the-map pricing today, from an $8 median price for forest carbon credits, to $1,100 for carbon capture and storage. The former prices will go up as standards and quality go up – and the cost of technology solutions like DAC and CCUS will drop dramatically with scale. Better quality and appropriately priced projects will provide critical investments to implement climate objectives.

Note: Reflecting disappointment in the failure of COP28 to achieve agreement on a trading exchange, the price of nature-based credits collapsed to below $1 but is now recovering.

Overall, there has been tremendous positive evolution in the voluntary carbon markets: improved transparency, common standards for credit quality and verification, evolution of trading platforms to facilitate growth, and growing convergence of markets and regulatory frameworks. All of these are essential for the enormous amount of climate work ahead. While not all goals for the market were realized at COP28, the progress made was substantial, and the stage is set for more to come.

In Part 2, we take a look at compliance markets and the concept of cap and trade. Click here for the full article.