Dear Friends,

Is the world failing the marshmallow test?

In the 1960s, a psychologist probed 4-year-olds’ ability to wait for greater reward (two marshmallows in the future) instead of leaping at immediate gratification (a single, tempting marshmallow on the plate in front of them). The study found that children who waited were more likely to flourish in the future.

In some ways, tackling climate change is similar. We are asked to restrain ourselves from what we are tempted to do – develop more fossil fuels, ranch on deforested land, continue carbon-intensive transportation and food production – in order to achieve the greater reward of a healthier, more economically secure planet in the future.

This challenge – to think long term and to value what we have to gain in the years to come, rather than being seduced by easier short-term temptations – is hard for us.

But what happens if we don’t resist the temptation to continue to put up greenhouse gas emissions at our current clip?

A new study shows a worrisome outcome. Adding to the plethora of reports from financial leaders like Swiss Re (the world’s largest insurance company), Deloitte, McKinsey, BlackRock, and others, this report from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research outlines huge hits to our global and national GDP if we continue on our current emissions trajectory. It predicts that global income will decrease about 19% in the next 25 years (about 11% for the U.S. GDP). Much of that loss will come from projected crop and human productivity declines, not just the cost of escalating natural disaster damage.

We understand that predicting future GDP can sound like reading tea leaves, but when the findings from such different financial experts are so consistent, they should not be ignored.

Keeping that in mind, how should we handle the very real threat of blackouts on our future grid? Some still say the solution is to add more fossil fuels, and that may sound reasonable – until you factor in the big picture. More fossil fuels on the grid may stabilize it in the short run, but this type of power needs consistent water sources, which are increasingly unreliable. Burning more coal, oil, and gas will lead to increased climate-related weather disasters and extreme warming – which will end up taxing the grid even further. And, as the Russian invasion of Ukraine showed us, fossil fuels are tied to global market prices and can be extremely volatile, driving up inflation and causing unexpected pain to household budgets.

The good news is that today’s renewables can provide much cheaper new power than fossil fuels in almost every nook and cranny of the world. True, they can’t do the job alone (though they can safely pick up quite a lot of the load – Iowa now gets two-thirds of its electricity from wind, thank you very much). We do need energy sources that provide power when the wind isn’t blowing and the sun isn’t shining, but they have to be a lot cleaner than today’s fossil fuels.

These new technologies are more difficult to integrate into our legacy systems and may be more expensive than the old, established ways of doing things, hence the ongoing quandary: How do we convince ourselves to hold out for something new, even if it is more expensive or difficult in the short run, to be more likely to flourish in the future?

Will we pass the marshmallow test?

Sincerely,

The C-Change Conversations Team

Notable Quote

“Despite all attempts to deny, conceal, gloss over, or relativize the issue, the signs of climate change are here and increasingly evident. No one can ignore the fact that in recent years we have witnessed extreme weather phenomena, frequent periods of unusual heat, drought, and other cries of protest.”

– Pope Francis

News of Hope

April showcased notable momentum in policy and society. The U.S. administration set severe limits on coal-burning power plants, addressing the “dirtiest” fossil fuel that emits the most emissions. Such regulations will accelerate our transition off of coal, which has already dropped behind both natural gas and renewables as a power source. Because coal production has become so automated, and natural gas has stolen its share in power generation, national employment in coal has dropped to around 40,000 (half of 2008 levels). These new regulations will accelerate that shift and we will need to be supportive of the states and communities that have depended on coal as a primary source of income. That said, it is critical to stop burning coal as quickly as is feasible, and other countries, including the seven leading industrialized nations (G7), have committed to phasing out coal by 2035.

This momentum may be helped by changes in how our legal systems are beginning to view climate change. In noteworthy cases in Switzerland and India, high courts have upheld that people have the “human right” to be safe from climate change impacts and that governments need to do more to meet climate goals. The U.S. also is seeing growing numbers of climate suits (though some are to block climate action), with 20 suits from states and cities against big fossil fuel companies expected to go to trial this year. Could it be that we are approaching a big tobacco/opioid crisis moment when it comes to holding institutions accountable for climate change?

There’s also real momentum in some unexpected places – like the scourge of plastic waste. Plastics, which are made from petroleum products, are so ubiquitous and so fossil-fuel dependent. Or maybe not. Oil companies have said that creating new plastics will be a major source of profit for them going forward – but what if we could generate “new” plastics without drilling for fossil fuels? “Advanced recycling” would turn dirty, mixed plastics into new plastics [paywall], over and over, significantly contributing to our decarbonization efforts.

Our enthusiasm for electric vehicles remains staunch, so we were thrilled to learn that we are now recycling 90% of EV batteries. It makes moot the argument of whether EVs are cleaner than combustion engine cars. Not only that, the batteries themselves are improving faster than we can say jack rabbit – they last longer, charge faster, and drive farther. In the not-so-distant future, we may even be able to charge EV batteries simply by driving, a vision that is in the works in India and parts of the United States. Now that’s cool.

So is the construction of the first all-electric skyscraper in Brooklyn, NY, where buildings are the main producer of carbon emissions. The 44-story apartment building has induction cooktops and a water-source heat-pump system, as well as smart thermostats to maximize efficiency. (For safety reasons, there is an emergency-only backup gas generator.) It’s being hailed as a potential model for low-emissions construction, demonstrating how the marketplace is adapting to climate change realities.

Also cool? Ski resorts across Europe are saving their future seasons by “snow farming.” It’s actually a centuries-old concept of insulating snow through the summer and it could save an economy that’s been traditionally dependent on cold temperatures to succeed.

Whether it’s hundreds of years old or fairly modern, there’s a tremendous upside to rethinking methodologies and technologies in terms of our transition. The U.S. administration took an encouraging step on the nuclear power front, partnering with the governor of Michigan to finance pulling an old power plant out of mothballs. It will be the first-ever nuclear power plant to reopen in the U.S., a potential boost for an industry that is critical to clean energy but has been struggling to bring new plants online.

News of Concern

April also brought news that, driven by rising ocean temperatures and El Niño, our coral reefs are experiencing a monumental global bleaching event – the fourth in three decades. Scientists are building a “Noah’s Ark” to save as many species as they can, but experts fear massive coral deaths, as the only real solution is to reduce our CO2 emissions.

We are largely unprepared for today’s extreme weather, but the recent flooding in the UAE and Oman was something to behold – Dubai received more than a year and a half’s worth of rain in less than 24 hours. Attribution scientists say the deluge was 10-40% more intense than would have been expected without climate change – and it’s likely these catastrophic rains will become more common as temperatures increase.

It’s also likely that we’re looking at another summer of smoky air. A warm, dry winter kept dozens of small fires ablaze across Canada and experts say we should expect that last year’s record-breaking wildfires were not a one-off.

There are myriad stumbling blocks to our transition. Sometimes our great climate-saving ideas turn out to have higher costs than expected, like the high-tech indoor farms that allow crops to grow almost anywhere, despite the extreme weather or conditions outside. They’re extremely efficient – and they are using a huge amount of power that’s mostly from fossil fuels. But we have to be patient – we’re still in the infancy phase of clean tech. It will mature and it will improve.

In the meantime, yes, we may take two steps backward as often as we move forward. Take for example the city of Berkeley, CA, which plans to repeal its landmark natural gas hookup ban, throwing into question similar restrictions in localities across the country. But the fact remains, electricity is cheaper than fossil fuels – and it doesn’t pollute the planet or make us sick. Once we recognize the value, we may not even need regulations to drive climate action because it will be clear that it’s the smarter choice to save both the world and our wallets.

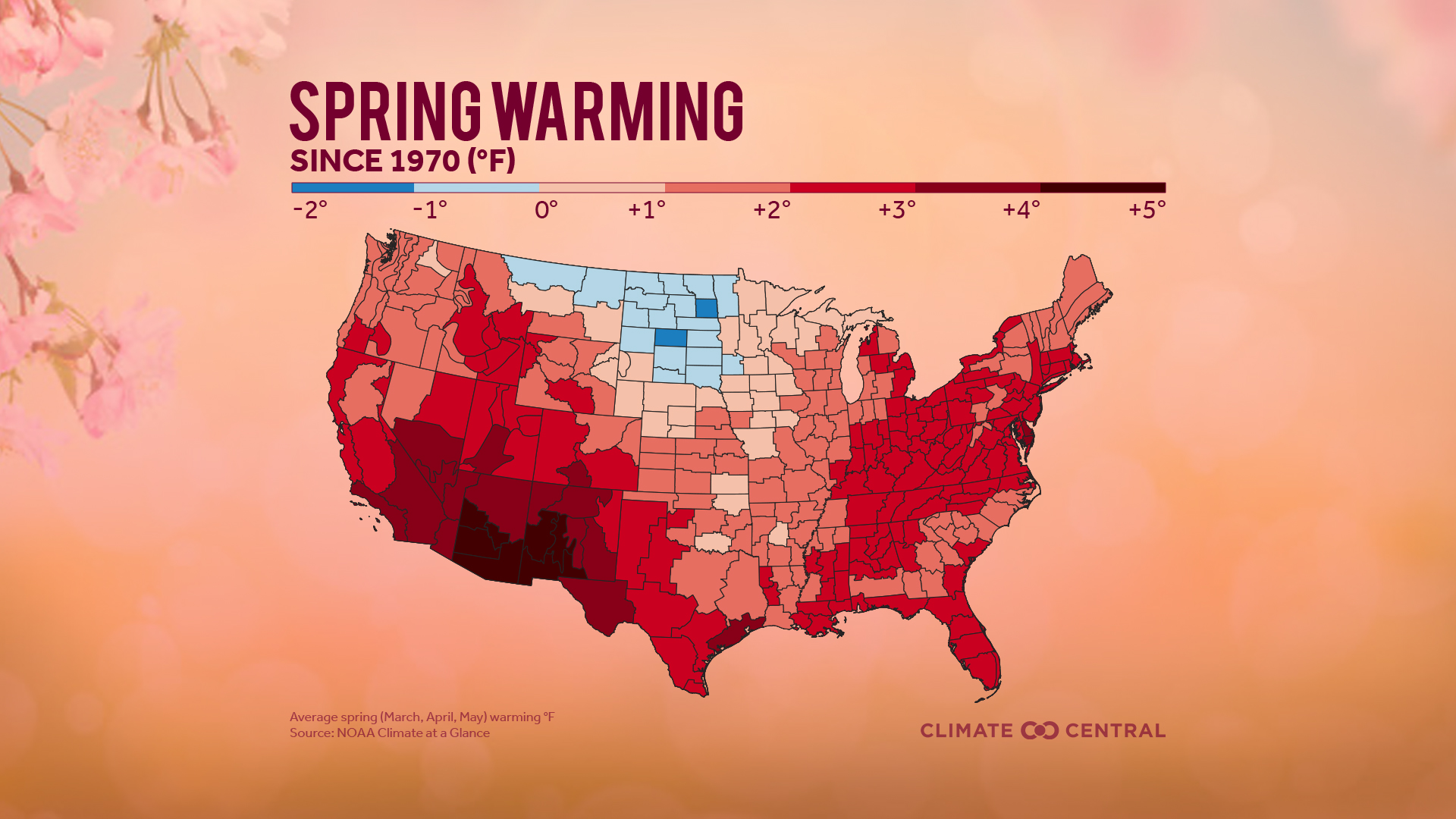

Notable Graphic

It’s not your imagination – spring feels warmer than it used to. On average, spring has become 2.2°F warmer in 229 U.S. locations since 1970. This directly affects our growing seasons, water supplies, and health.

Notable Video

April showers bring May flowers – and those flowers bring so much pollen. The spring allergy season has become 20 days longer, with pollen concentrations up 20% due to warmer temperatures, more rain, and higher levels of CO2. This report from “NBC Nightly News” takes a look at what allergy sufferers can expect as climate change impacts us.