Dr. Joan Schiller, a medical oncologist who is internationally recognized for her work in lung cancer clinical research and a member of the C-Change team, responds:

![]()

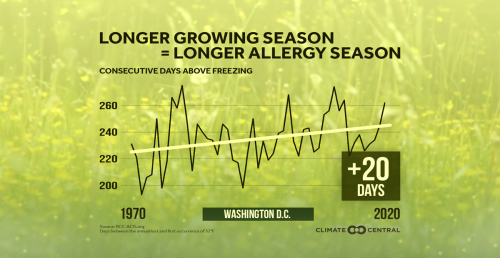

Alas, yes, it is true. For two reasons. First, thanks to a warming climate, the pollen season is becoming longer. Spring-like temperatures are starting earlier, and fall-like temperatures are starting later, and with a longer growing season comes a longer allergy season. Climate Central found that over the past 50 years, the growing season lengthened in 82% of the places analyzed and extended by at least four weeks in 38 of those places. Two areas – Bend, OR and Reno, NV – had 99 additional growing-season days!

And while that sounds like great news for the agricultural sector, it isn’t. Climate change is also changing water availability – producing both more heavy, damaging rains and drought – and pushing crops against their heat thresholds, which will lead to decreased yields in the future.

![]()

Climate change also affects the intensity of the allergic response. The amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere directly impacts pollen concentrations because it can stimulate plant growth. One study reported that pollen levels doubled when carbon dioxide levels were increased from current levels (about 400ppm) to 800ppm and that elevated levels of CO2 increased the amount of pollen produced by about 50%. Needless to say, with 10-30% of the population affected by nasal allergies and more than 300 million affected by asthma, this is a major problem which is likely to get worse.

![]()

Skin allergies also are affected by climate change. For example, there is a correlation between exposure to house dust mites found in mattresses and bedroom floors with temperature, humidity, and skin allergies. Warmer temperatures and increased humidity also exacerbate eczema, contact dermatitis, hives, and angioedema. Plus, as CO2 levels in our environment increase, so do woody vines, such as poison ivy.

![]()

Mold is another source of allergens. Mold growth increases where there are higher levels of precipitation and flooding, which are both on the rise due to climate change. In the wake of Hurricanes Katrina and Rita in 2005, for example, heavy mold growth was identified in 70,000 water-damaged homes. Infants exposed to mold before one year of age are nearly three to four times more likely to develop asthma and in children and adults, exposure to molds can lead to a stuffy nose, wheezing, and red or itchy eyes, or skin.

The most vulnerable populations bear much of the burden of increasing asthma and allergies. Effective medications and therapy to manage symptoms can be a burden on lower-income families, especially since asthma is more prevalent in families living below the poverty line. Currently, the highest asthma diagnoses, hospitalizations, and deaths are disproportionately found in minority communities due to a combination of factors, one of which is discriminatory housing policies restricting minorities to older, less ventilated homes and neighborhoods with elevated levels of air pollutants.